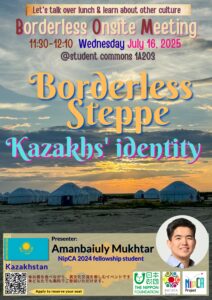

The 13th Borderless Onsite Meeting was held on Wednesday, July 16, 2025.

This time, Mr. Amanbaiuly Mukhtar, a 6th cohort NipCA fellow from Kazakhstan, gave a compelling presentation titled “Borderless Steppe: Kazakhs’ Identity.” The event explores the dynamic intersections of culture, memory, and identity in Kazakhstan and the broader Central Asian region.

To open his presentation, Mr. Amanbaiuly invited the audience to feel Kazakh identity through sound playing the dombyra performance of “Men Qazaqpyn” (I am Kazakh), a widely regarded known Kazakh song. The powerful music, rich with emotion and cultural resonance, reflects the resilient spirit of the Kazakh nation, whose identity has been “died a thousand times, and reborn a thousand more.”

The presentation journeyed into the geographic and historical roots of the Kazakh people, tracing their origins to the Altai Mountains, a region that today spans Kazakhstan, China, Mongolia, and Russia. Widely acknowledged as a cradle of Turkic civilization, this area holds symbolic and cultural weight as the birthplace of nomads. Mr. Amanbaiuly emphasized that Kazakh identity was not formed in isolation. It emerged from a rich blend of Turkic, Mongol, and Iranian tribes, shaped by both historical migrations and cultural synthesis. Archaeological evidence in the Altai continues to tell stories of early nomadic life, reinforcing the region’s role as both a mythical origin and a tangible homeland.

The etymology of the word “Kazakh” (Қазақ) was another focal point. Derived from ancient Turkic roots, the term is commonly interpreted as “free man” or “independent,” from the word qaz, meaning “to wander.” This connection to freedom and mobility reflects the essence of Kazakh nomadic heritage—a people who roamed the steppe, unbounded and self-reliant. The term first gained prominence during the formation of the Kazakh Khanate in 1465, when leaders Janibek and Kerey broke away from the Uzbek Khanate, uniting various nomadic clans and establishing a political structure that would become central to Kazakh ethnicity.

Mr. Amanbaiuly then explored the symbolic and political significance of the Great Steppe in Kazakh national consciousness. He noted that in the post-Soviet period, Kazakhstan initially embraced an ethnocentric narrative centered on the steppe as a civilizational core. Over time, however, this approach evolved into a more inclusive interpretation, recognizing the diversity of cultures and peoples who shaped the steppe’s history.

Today, the Great Steppe narrative functions as a cultural framework used to connect ancient traditions with modern identity and to legitimize Kazakhstan’s historical continuity within the Eurasian space.

The presentation concluded by emphasizing that Kazakh identity is not static but living, dynamic, and resilient. From its nomadic foundations and political formations to modern expressions of nationhood, the Kazakh story continues to evolve—shaped by memory, culture, and the enduring call of the steppe.