On Tuesday, October 14, 2025, the NipCa Project hosted its 15th Borderless Onsite Meeting (BOM), bringing together curious minds from around the University of Tsukuba. The main highlight was a captivating presentation by Muhammadibrokhimov Botirjon, a second-year master’s student, who stepped into the spotlight as a guest speaker.

On Tuesday, October 14, 2025, the NipCa Project hosted its 15th Borderless Onsite Meeting (BOM), bringing together curious minds from around the University of Tsukuba. The main highlight was a captivating presentation by Muhammadibrokhimov Botirjon, a second-year master’s student, who stepped into the spotlight as a guest speaker.

His talk, titled “Uzbekistan Behind the Curtain: Customs, Human Relations, Day-to-Day Practices and Overlooked Points,” offered attendees a rare glimpse into the lesser-known facets of Uzbek life. From the nuances of human relations to everyday customs, Mr. Muhammadibrokhimov guided international students through stories and survey research insights that peeled back layers of knowledge surrounding Uzbekistan, often overlooked by foreigners.

Before diving into cultural nuances, Mr. Muhammadibrokhimov began with a quick introduction to Uzbekistan – a nation often described as the heart of Central Asia. Home to over 36 million people, Uzbekistan is one of only two doubly landlocked nations in the world, with long, hot summers and mild winters, making it a land of contrasts, not just culturally but environmentally. Uzbekistan’s identity is deeply rooted in diversity. While Uzbek is the official language spoken by about 74% of the population, Russian and Tajik also play significant roles in daily communication. Religiously, the country is predominantly Muslim (88%), alongside smaller communities of Eastern Orthodox Christians and other faiths.

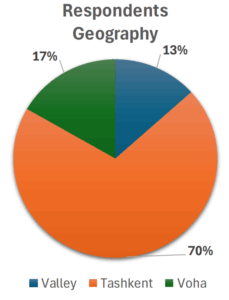

Mr. Muhammadibrokhimov highlighted a critical point: when foreign countries are portrayed in global media, the narrative often reflects only one side of the coin. While not necessarily negative, this limited perspective can leave gaps in understanding. To truly navigate life in a different culture, one needs access to the other side of the coin—the subtleties that rarely appear in headlines or quick online searches. Thus, the mission was to think critically, encourage multiple viewpoints, and provide a window into people and society beyond surface-level facts. As a matter of fact, Mr. Muhammadibrokhimov came to the BOM event prepared with a survey and interview results of Uzbek people from different regions (see Figure 1) and aligned the quantitative and qualitative analysis most engagingly.

Figure 1. Survey Respondents Geography.

The first main part of the presentation explored greetings – both verbal and non-verbal – and how they vary across regions like Fergana Valley (the eastern part of Uzbekistan consisting of Andijan, Namangan and Fergana), Voha (the western and southern parts of Uzbekistan), and Tashkent. By showing the Greeting Pyramid of Uzbekistan, students were introduced to the greeting phrases and how they differ based on the level of closeness with Uzbek person. To get a practical touch, Mr. Muhammadibrokhimov showed a one-minute video of two Uzbek friends casually greeting each other on the street and analysed both their verbal and non-verbal languages. Non-verbal cues – such as a respectful nod or placing a hand over the heart – are common and convey sincerity and respect, values that remain central across Uzbek society. However, when it comes to friends and acquaintances, people usually prefer to hug each other (usually same gender, but male and female greetings are more reserved and respectful).

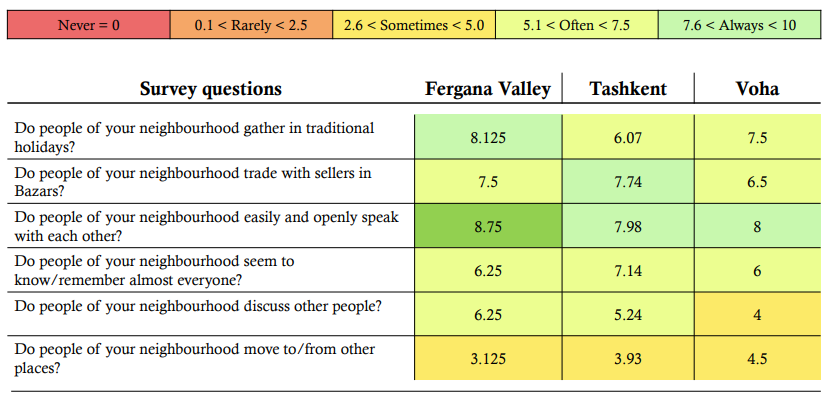

Then, Mr. Muhammadibrokhimov conducted a comparative analysis of how two very important aspects of Uzbekistan differ across three regions: the trading/bargaining in Bazars and the concept of “neighbourhoodism” (from Uzbek – “qo‘shnichilik”).

Bazars are special trading places in Uzbekistan where people can buy various household products, but one distinguishing element from other countries is that prices there are not fixed, and people bargain a lot. In Uzbekistan, trading is one form of art. It is not about how many resources you have, but how resourceful you are with what you have. As an example, Mr. Muhammadibrokhimov provided a part from an interview with a Japanese tourist who has been to Tashkent Chorsu Bazar:

“I have been in Tashkent Chorsu Bazar and was overwhelmed with both the size of the place and the range of products people sell. I’ve managed to buy some things, but, for the first time, had this strange feeling that I have overpaid.”

“Neighbourhoodism” is about taking care of your neighbours, knowing and visiting them on special occasions, which are a lot in Uzbekistan, especially in mahallas (countryside villages). There is a quote in Uzbekistan which says, “Seven neighbours/villages for one child’s growth”. This means that because of the closeness and warm relations of neighbours, children usually treat elderly people very respectfully and expect to learn from them the customs. There is an invisible responsibility of elderly people to teach youth about human relations, especially when youth make mistakes or mistreat someone. Mr. Muhammadibrokhimov dived deeper and presented how these customs differ across three regions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Comparison Table of various aspects of “neighborhoodism” and trading.

Of course, it is difficult to express everything from the presentation briefly in a written form here, but overall, the presentation has been conducted for the purpose of showing that there is more to Uzbekistan than the internet posters and popular images, mostly gone through rigorous filters. The survey results and interviews aided the content with data and evidence. At the end of the presentation, students had an opportunity to engage in discussions and ask questions about the areas of their interest on the topic.