Otkulbek kyzy Akylai

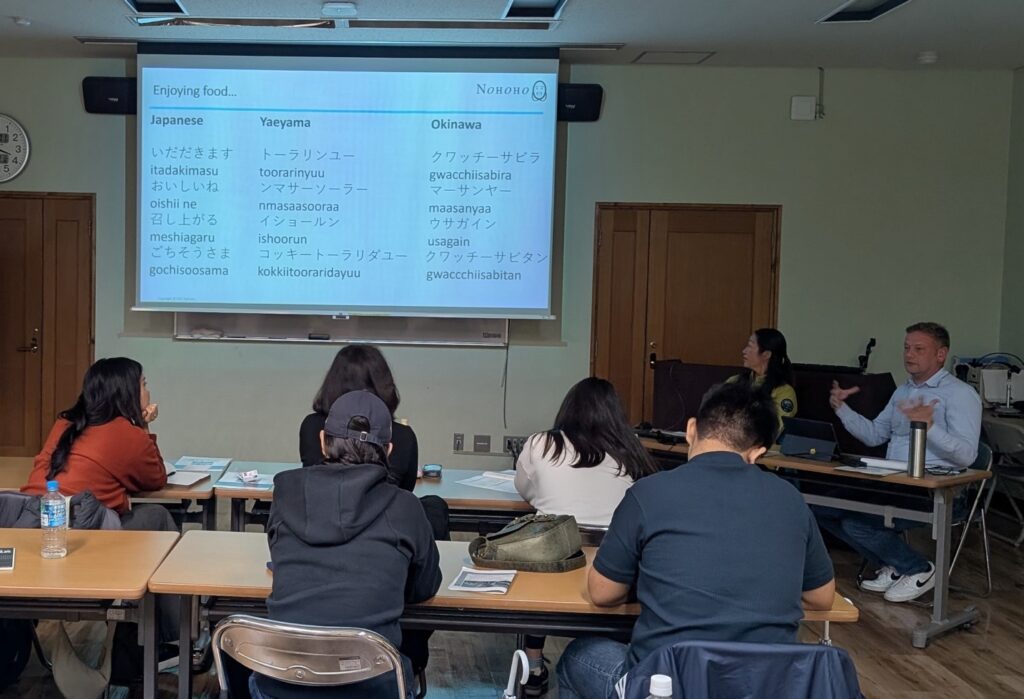

In this reflective essay I will share my personal discoveries at Eric van Rijn’s lecture that was a part of our study trip to Yaeyama Islands. Yaeyama region is profoundly distinct from Okinawa and mainland Japan. We had the privilege of attending a lecture by Eric, who immersed us into the history, language, and cultural landscape of the Yaeyama region.

History

Yaeyama’s history was rich with events. The islanders experienced, the Oyake Akahachi Rebellion, which symbolized local resistance, to the Satsuma invasion, the Meiwa Great Tsunami, while the abolition of the Ryukyu Kingdom and the creation of Okinawa Prefecture marked yet another profound transformation. More recently, the end of U.S. occupation signified a moment of reclamation.

The islands have faced political, environmental, and social changes since the 14th century, adapting after the Ryukyu Kingdom was established in the 1500s. Mr. Eric van Rijn has showed us that the language carries history.

A Language on the Brink

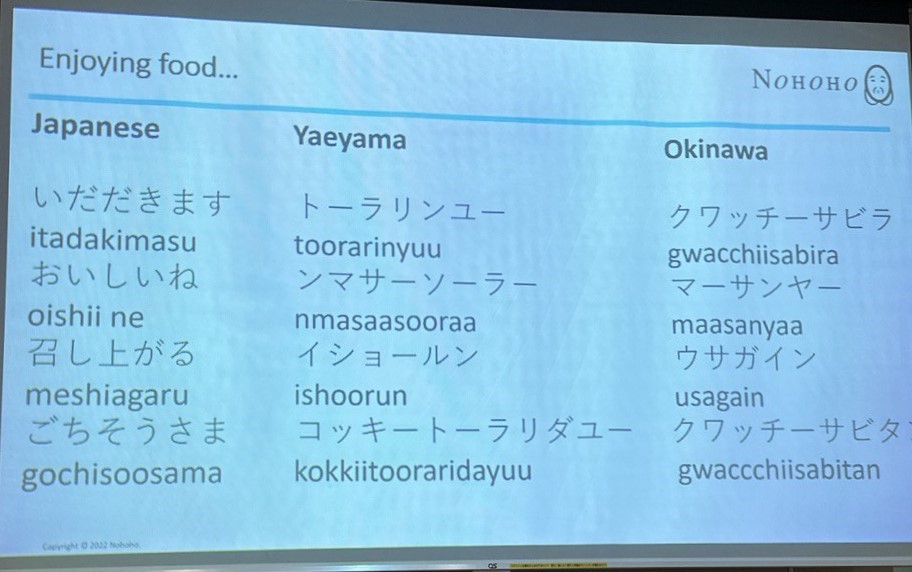

The Yaeyama languages, part of the Japonic language family, are rich with dialects. There are four villages dialects such as Yaeyama, Tonoshiro, Okawa, Arakawa. Moreover, there are 600 dialects in 600 villages. Now, UNESCO recognizes six Ryukyuan languages, highlighting the urgency of preservation efforts.

Language is more than just words – it is a carrier of culture, it is a vessel of stories, songs, festival rituals, and other oral traditions that form the cultural soul of Yaeyama islanders. The languages are not preserved in textbooks; the languages exist only as long as there are speakers to share them. When the language disappears so does the way of understanding the world through that language. As part of an exercise, we took a small step in engaging with the language by learning how to introduce ourselves in Yaeyama dialect.

Reflections on Sustainable Heritage

Beyond the cultural enrichment, this experience raised broader questions about the intersection of language preservation, tourism, and sustainable development. If culture is a key asset of Yaeyama, could sustainable tourism models emerge that center indigenous languages as part of immersive cultural experiences? Such models could provide both economic opportunities for local communities and a means of incentivizing language preservation.

This site visit was incredibly important for me, because it aligned with my MA thesis on intangible heritage, indigenous knowledge transfer. So I found myself asking: how can intergenerational knowledge transmission be supported? What roles do families, schools, and communities play in ensuring that young people inherit the linguistic and cultural richness of their ancestors? For those of us engaged in oral studies and indigenous knowledge, the Yaeyama experience offers valuable insights. How do we document oral traditions properly with full respect to nuances, emotions, and context?

A Meaningful Investment

For me, this journey was a physical immersion into a scenario of what is at stake when languages and cultures are endangered. Thanks to the generous support of those who made this program possible, we were able to engage not just intellectually, but personally, with the challenges and opportunities of language and culture preservation. The experience has left me not only with knowledge but with a sense of responsibility and a lot of food for thought.