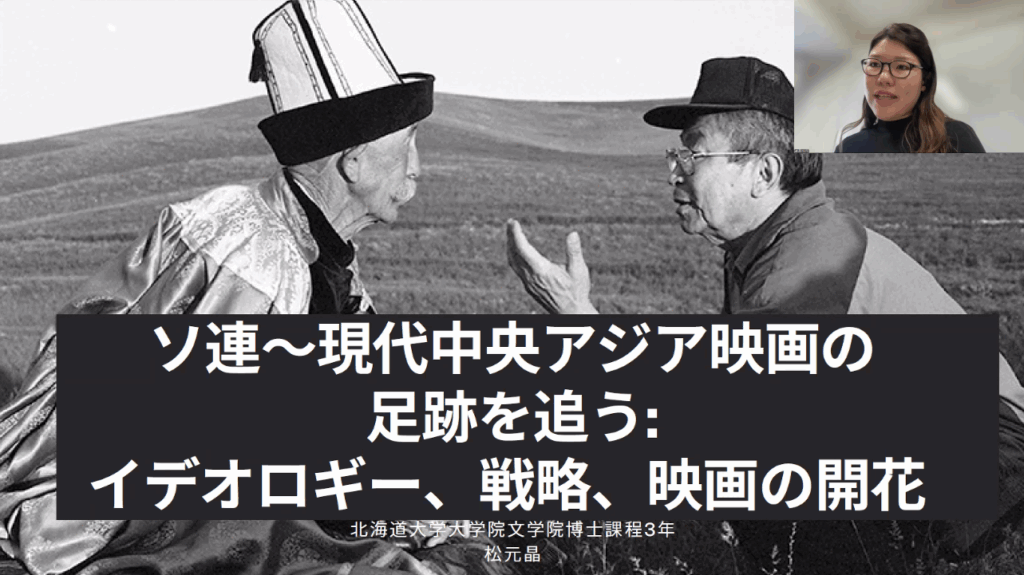

On Thursday, February 27, 2025, the 53rd Public Lecture on “The Future of Central Eurasia and Japan” was held, and Dr. Matsumoto Akira, a third-year doctoral student at the Graduate School of Humanities and Human Sciences, Hokkaido University, was invited to give a lecture entitled “Tracing the Footsteps of Soviet to Modern Central Asian Film: Ideology, Strategy, and the Blossoming of Film.”

Ms. Matsumoto research Soviet films. From 2019 to 2022, while working as a commissioned instructor under the “Grant Assistance for Grassroots Human Security Projects” at the Embassy of Japan in Kazakhstan, she also built connections with Kazakhstani film through research. Currently, she is focusing on films from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan from the 1960s, and are researching the representations and their backgrounds found in these films as well as the activities of the filmmakers.

Central Asian cinema has a history of producing films that utilize complex backgrounds, acknowledging the existence of Russian centrism and cultural hierarchies, rather than establishing identity through comparison with other countries or peoples. In the Soviet Union, film was also considered the most important art form and played a role in spreading ideology. Focusing on these points, she talked about the relationship between Central Asian film and ideology, the changes in representation and social background, and the activities of Central Asian filmmakers.

Central Asian cinema began surprisingly early, in 1908, and from the very beginning it was believed that film had political power. In the 1920s, many works influenced by Soviet film trends such as criticism of tradition, women’s liberation, and revolutionary ideas were produced. On the other hand, Central Asia was often portrayed as an “uncivilized existence” in Soviet films. For example, in the film “Turksib,” stereotypical ideas and the fact that Central Asia is uncivilized are clearly depicted.

The 1930s saw the development of film culture to such an extent that it would later be called the foundation of Uzbek cinema. During the war, technical and performance guidance was received from evacuated Russians, leading to further advancements in film production. In the postwar 1960s, along with the revival of Soviet cinema, film also developed in countries such as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. It seems that Kyrgyz films in particular were quite popular internationally.

In the 1980s, the influence of perestroika allowed for greater freedom of expression. And along with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, she explained the overall flow of history in which all Soviet cinema faced an identity crisis of “what should be created?”

In this way, Central Asian films have continued to adapt to the flow of history, adapting to, criticizing, and utilizing Soviet ideology. She mentioned that while constantly keeping an eye on the trends in the Soviet center and developing film art within that framework, there was also a visible attitude of trying to break the stereotypes held by each country.

During the Q&A session, questions were raised about popular and historical films in Kazakhstan, why it was said that women could not produce art films in the 1950s, and the current positioning of Central Asia in Russian cinema.