Russian and Kazakh language training report

School of Humanities and Culture, College of Humanities

Nomura Ruina (1st year)

1.Introduction

I participated in the Russian and Kazakh language training program in Kazakhstan from 2/16 to 3/23. Here, I will describe my actual experiences, especially about food, learning Russian, etc.

2.Local Meals

While there, I stayed in a homestay. I usually had breakfast and dinner at my homestay and lunch in the university cafeteria.

The meals consisted mainly of bread (fried breads such as samsa, balsak, and piroshiki, as well as black bread, white bread, lepioshka, etc. – the variety is incomparable to that in Japan), dairy products, and meat, and I got the impression that there were very few vegetables. It seems to be very high in calories, but it’s delicious. Prices are the same or slightly lower than in Japan, but meat and other items are probably much cheaper. I got the impression that it was a mix of Kazakh and Russian cuisine. According to my host father, “In Kazakhstan, we eat Russian food, and in Russia, we eat Kazakh food.” The host family reduced the portions they ate to prevent obesity.

Figure 3 Bought at a bakery Figure 4 Ice Cream

3.Learning Russian

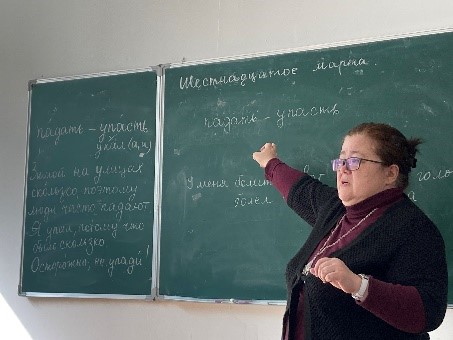

Figure 5 Russian language class

Figure 6 Russian Textbooks

While I was practicing my instrument at my homestay, my host brother came into the room to iron something. He looked at my performance and said “prekorna” (I later found out that it was the word Прикольно, but it sounded like that at the time). At the time, I didn’t understand what it meant, but I thought it was probably a compliment, something like “amazing” or “cool.” On another day, I bought a fish hat like Sakana-kun and showed it to another host brother, and he also said “prekorna.”

Figure 7 прикольно hat

From these two examples, I thought that “prekorna” was probably a compliment, and that it was more general than Japanese expressions like “cool” or “amazing” and had a similar meaning to “like.” So, to try it out, when a local Russian speaker showed me some travel photos, I said, “prekorna ?” His response was something like, “Прикольно is correct. Although I didn’t fully grasp the exact nuance, I learned that there is a word called Прикольно that can be used as a compliment.

I think the good thing about going to a local place is that you can guess how to use all the words that your host family, passers-by, and friends have said as example sentences, as well as what you have learned in class, and you can check whether your usage is correct by actually saying it to the locals.

When I was there, I looked up the necessary words and expressions for the topics I wanted to talk about, such as the events of the day, and wrote them on the back of my hand before going to dinner. Probably no more than 10% of the words can be memorized in a single session, but by increasing the number of simple encounters with words, we have increased that 10% (I intend to).

I was a little impressed that I could understand what the Russian teachers were saying in my Russian classes after I returned to Japan.

4.Looking back

The main people involved within the training included English lectures at the university, conversations with host families, and interactions with Russian language learners

The Russian language learners who attended classes together were a group of students of different nationalities, ages, and backgrounds, including Chinese speakers, Korean speakers, Japanese, and Turks. There were Kazakhs who had moved to live with relatives from Urumqi, China, and students who had started learning Russian because they had started living in Kazakhstan, and other students who would never have met in a university or Japan environment.

In conversations with these people and host families, they will inevitably talk more about their own backbone and the culture and customs of Japan than in conversations with Japan. In addition, participants were asked to give their opinions on more in-depth topics such as the international relations between Japan and its neighboring countries, and historical events related to Japan, such as perceptions of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

When I am in Japan, the fact that I am Japanese is so self-evident that it is not an issue, but when I go abroad, I am undoubtedly Japanese, and I have come to realize through my interactions with local people and people from other countries that I am expected to have a certain understanding and perspective on Japanese culture, history, and international relations.

Currently, my knowledge is limited to generalities, and I have not yet reached the point where I can express my own opinions, make comparisons with other countries, or engage in discussions. I was keenly aware of the need for this type of literacy, which is the minimum required of “Japanese” internationally.

The official languages in Kazakhstan are Russian and Kazakh, but when discussing such topics with people of other nationalities, English was the most commonly used language. English is the most significant language not only in conversation with native speakers, but also in communication among non-native speakers. If we can become able to express our opinions at the very least in English, and ultimately in Russian, I believe we will be able to fulfill the role of Japanese people that is expected of us overseas and in Central Asia.

What I wish I had brought with me is a mobile battery. It’s relatively troublesome when the battery runs out.

5.Conclusion

Personally, this training was very meaningful for me. In a short period of time, my Russian proficiency improved beyond what I could have done while I was in Japan, and I was able to meet people I would never have met in Japan or even known existed. Although our cultures are certainly different, I felt that at least among those of us living in modern cities, what makes us happy and what makes us sad is not that different. Once I realized that, I no longer felt afraid of interacting with people I didn’t know.

Figure 9 Snow fell in March Figure 8 в магазине

Figure 10 View from the house