Otkulbek kyzy Akylai

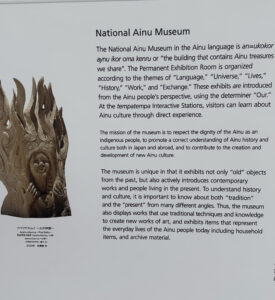

The National Ainu Museum and Park, widely known as Upopoy (ウポポイ), was established in 2020 in Shiraoi, Hokkaido, with a mission to promote understanding, respect, and recognition of the indigenous Ainu people’s culture and history. The word “Upopoy” itself means “singing together in a large group” in the Ainu language, a fitting title for a site built around collective memory, cultural healing, and the revitalization of indigenous identity. Far more than a traditional museum, Upopoy stands as a cultural complex and a political statement: an attempt by the Japanese state to reckon with its colonial past and offer a platform for marginalized voices.

We visited the museum on a sunny day, and our first collective impression was one of awe—not just at the content, but at the scale of the grounds. Set besides a large lake and surrounded by a forest, the museum harmoniously blended in with the nature.

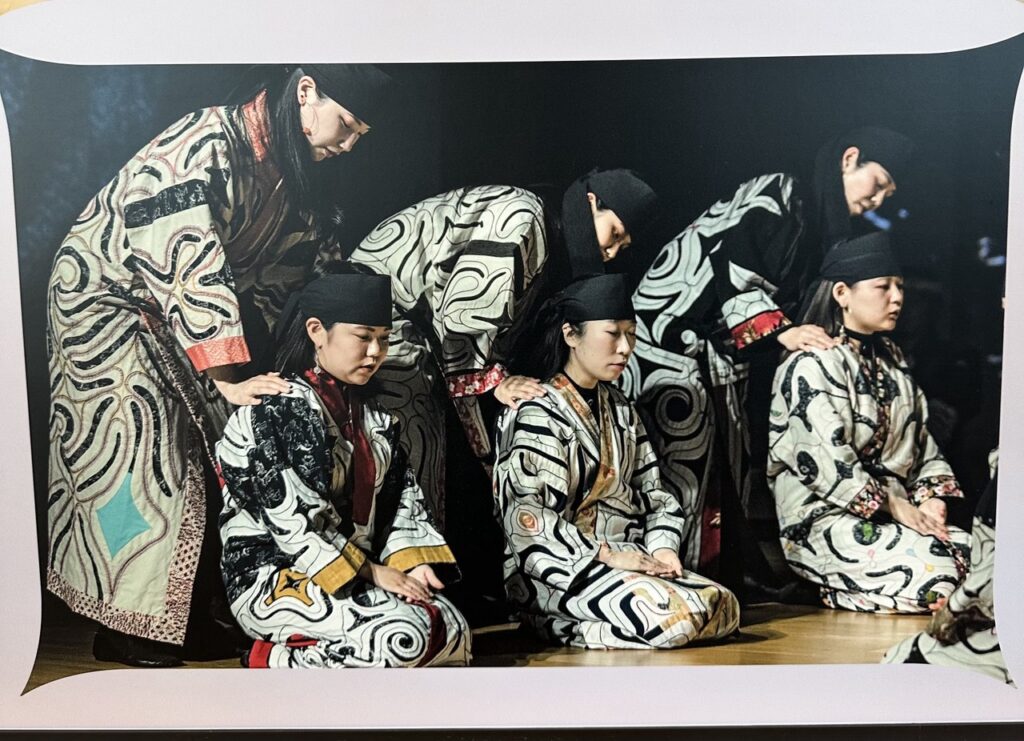

The immersive activities brought history to life in an exciting way. We tried traditional Ainu archery, walked through reconstructions of Ainu homes with decorations that mimicked a real home, and even dressed in their embroidered traditional garments.

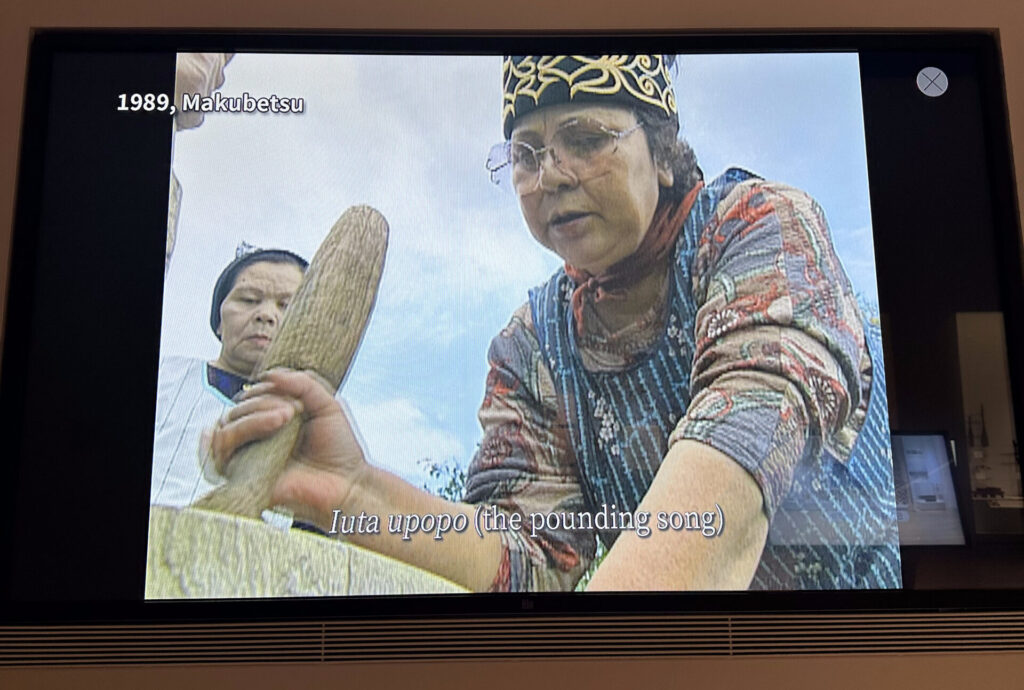

One of the most intellectually and emotionally impactful parts of the visit for me was encountering Ainu spirituality. I listened to their hauntingly beautiful songs and learned about their animist beliefs, which is a world where each river, bear, or tree holds a kamuy – spirit. The performance of singing and dancing was mesmerizing to say the least. To me, it was not just art, it was a spirit of the people. I am honored that I was able to observe a real life performance of Upopoy – it made us connect to Ainu through songs and feelings. It was far more than a mere entertainment, it was a sacred ceremony.

The Ainu people, indigenous to Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands, endured historical marginalization and assimilation, especially under Meiji-era policies that stripped them of land, language, and cultural identity. Today, efforts like Upopoy represent a slow but necessary shift towards reparative justice and recognition of indigenous people and their voices.

A moment of personal resonance came when I saw the Ainu mouth harp—a small, vibrating instrument played with breath and tension. It was just like our metal and wooden jaw harp (temir and jygach ooz komuz) in Kyrgyz culture, an instrument I’ve known since childhood. This reminded me that such small things can serve as a bridge across continents; indigenous peoples have always been connected, not through globalization, but through ancient history.

As a graduate student studying sustainability, I derived several lessons for myself. First, sustainability must include cultural survival, not just economic or environmental metrics. Increasing GDP and lowering emissions is essential, but so is protecting oral histories, languages, and indigenous knowledge systems. Second, education should not be neutral or sanitized. Museums like Upopoy demonstrate that education can be emotional, political, and deeply personal. And we should be able to tell stories of the past freely: if we learn history, we might not repeat the same mistakes again.