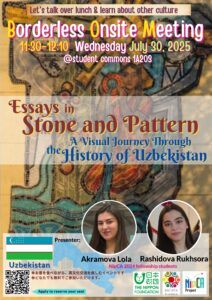

The 14th Borderless Onsite Meeting was held on Wednesday, July 30, 2025.

The session explored the deep connections between architecture and identity in Uzbekistan through a presentation titled “The Silent Language of Stone: Tracing Uzbekistan’s Identity Through Architecture.” Delivered by NipCA Fellows Rashidova Rukhsora and Akramova Lola, the presentation traced how material structures — from early fortress-cities to Timurid masterpieces and Soviet monumentalism— have served as instruments of governance, spirituality, ideology, and cultural continuity. Through this lens, Uzbekistan’s architectural heritage was presented not merely as visual ornament but as a living record of civilizational shifts.

The foundations of Uzbekistan’s built environment were laid in the pre-Islamic era. In the oasis-based states of Ancient Khorezm, architecture responded to both abundance and threat. Sites like Toprak-Kala and Djanbas-Kala reveal a spatial logic shaped by two forces: the fertility of irrigated land and the danger of nomadic raids. Architecture here prioritized defense, governance, and visual control of territory. At the same time, in the southern region of Termez, Buddhist complexes such as Fayaz Tepe embodied a contrasting ideal. Centered around stupas, monasteries, and contemplative courtyards, these structures reflected a culture of inwardness and monastic discipline.

The arrival of Islam in Central Asia redefined the meaning and purpose of architectural space.

The arrival of Islam in Central Asia redefined the meaning and purpose of architectural space.

Beginning in the 8th century, cities were reshaped to align with Islamic conceptions of community, law, and sacred order. Under the Karakhanid and Khwarazmian dynasties, new forms emerged: mosques, madrasahs, mausoleums, and minarets. These were not simply religious institutions but cultural anchors, embedding shared values into the everyday structure of urban life. Geometry, calligraphy, and light were employed not as decoration, but as vehicles for spiritual reflection.

The Timurid period (14th–15th centuries) elevated Islamic architecture to cosmic proportions.

Architecture became a manifestation of dynastic ambition and metaphysical vision. Buildings such as the Sher-Dor Madrasah and the Gur-e-Amir Mausoleum were constructed on monumental scales, combining symmetry, color, and calligraphic artistry to express the harmony between spiritual and worldly power. The intense use of turquoise tiles, muqarnas domes, and symbolic geometry reflected not only aesthetic achievement but also a theological worldview — one that sought to map the heavens onto the earth through built form.

The 19th century marked a shift toward European forms under Russian imperial expansion.

As Central Asia was incorporated into the Russian Empire, architecture began to serve colonial administration and economic infrastructure. New typologies appeared: railways, banks, residences for imperial elites. The Palace of Prince Romanov and the Tashkent branch of the Imperial State Bank exemplify this period, where neoclassical façades and urban planning grids were layered onto Islamic cityscapes. Yet these structures did not erase local identity; rather, they added another architectural vocabulary to the region — one that reveals how power was negotiated visually between colonizer and local tradition.

In the Soviet period, architecture became a tool of ideological projection, yet local adaptation persisted.

The 20th century introduced a radically different aesthetic, one characterized by mass housing, monumental state buildings, and a focus on functional uniformity. However, Uzbekistan’s architectural expression did not vanish under standardization. Buildings such as the Navoi Grand Theater, partially constructed by Japanese prisoners of war, and the Tashkent Metro, with its richly ornamented stations, integrated Uzbek symbolism into socialist modernism. A particularly notable example is the State Museum of History of Uzbekistan, where abstract geometric forms and the symbolic cube — representing eternity in Eastern cosmology — were used to merge traditional meanings with modernist language. In these cases, ideology was not simply imposed; it was interpreted and localized.

Contemporary spaces in Uzbekistan also preserve narratives of international memory and human connection.

Two specific cases illustrate the intersection of architecture and postwar cross-cultural history. In Yangiabad, a small museum commemorates the contribution of Japanese POWs to Uzbekistan’s post-WWII reconstruction, reminding visitors of silent resilience and shared humanity. Meanwhile, in Rishtan, a town famous for ceramics, a Japanese language school was established through the friendship between a local craftsman and a visiting Japanese businessman. These sites, though modest, form a quiet architecture of memory — intangible, yet enduring — and demonstrate how built environments can reflect not only national identity, but transnational empathy and collaboration.

The presentation concluded by emphasizing architecture as a living record of identity in motion.

Uzbekistan’s buildings do not merely represent the past; they embody ongoing dialogues between tradition and modernity, the sacred and the political, the local and the global. Whether formed in clay, tile, concrete, or human relationship, architecture in Uzbekistan continues to speak — not only in the language of stone, but in the language of spirit, memory, and connection.