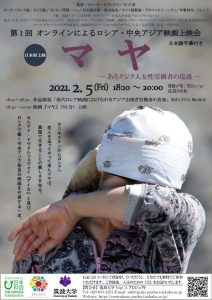

On Friday, February 5, 2021, the first online screening of Russian and Central Asian films was held. This is the first of a new project to introduce films that have not yet been introduced in Japan with subtitles, in order to deepen the understanding of Central Asian culture and the SDGs. For this year’s screening, we used Zoom to make commentary of the film in advance and then moved to Vimeo to show the film in high-definition. 522 people applied, which was more than the 500 capacity of Zoom, so we decided to direct those who applied after 500 to Vimeo, where there is no capacity limit, and let them watch the film only. The screening was very well received right from the start of the publicity, and it became the largest online event ever for NipCA project.

In the commentary before the screening, Dr. Kajiyama Yuji, the NipCA project coordinator and UIA who planned the project, gave a lecture titled “Representation of Central Asian Migrant Workers in Contemporary Russian Films.” In the first half of the commentary, he analyzed how immigrants from Central Asia are depicted in contemporary Russian video culture, referring to Sergey Dvortsevoy’s “Ayka (My Little One)” (2018) which was also screened in Japan, and explored the works of the past decade or so, when the number of immigrants from the region has increased. In the second half, he introduced Ms. Larisa Sadilova, the director of the film “She” (2013) to be screened, and explained some of the scenes on the environment and customs of Tajik immigrant workers. For example, in the first half of the film, there is a scene in which men, in turn, pass money to Rakhmad, a broker-like presence of Tajik workers, and write that amount into his note. This is the scene where they are giving money to their families in Tajikistan through Rakhmad. In the 1990s, shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was pointed out that there was no bank money transfer system to Tajikistan and that there were vendors who delivered cash by hand in this way.

In the commentary before the screening, Dr. Kajiyama Yuji, the NipCA project coordinator and UIA who planned the project, gave a lecture titled “Representation of Central Asian Migrant Workers in Contemporary Russian Films.” In the first half of the commentary, he analyzed how immigrants from Central Asia are depicted in contemporary Russian video culture, referring to Sergey Dvortsevoy’s “Ayka (My Little One)” (2018) which was also screened in Japan, and explored the works of the past decade or so, when the number of immigrants from the region has increased. In the second half, he introduced Ms. Larisa Sadilova, the director of the film “She” (2013) to be screened, and explained some of the scenes on the environment and customs of Tajik immigrant workers. For example, in the first half of the film, there is a scene in which men, in turn, pass money to Rakhmad, a broker-like presence of Tajik workers, and write that amount into his note. This is the scene where they are giving money to their families in Tajikistan through Rakhmad. In the 1990s, shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was pointed out that there was no bank money transfer system to Tajikistan and that there were vendors who delivered cash by hand in this way.

From the post-screening questionnaire, we learned that participants had signed up for the screening for a variety of motivations, including SDGs, Russia and Central Asia, migrant labor, women’s labor, and films. Since there are very few opportunities to see films related to Central Asia in Japan, it seems that it was the first opportunity to hear the Tajik language by most viewers. Most of the audience liked the film very much, and from the last scene, many people found hope for Maya’s future. We have already received many requests for a second event. It is disappointing that we cannot see a film on a large screen, but some of the applicants were high school students living in rural areas and people living abroad. Online screenings also have the advantage of bringing works to a wider audience.

Various events have gone online in the Corona disaster, but there is an impression that online movie screenings are still in their technical infancy, partly because Zoom is not suitable for streaming video. Many people have asked for more detailed commentary after the screening, but this also requires a format more suitable for online screenings. In the future, we plan to continue the screenings while trying out various screening forms and having a system which allows more applicants to participate.