Muhammad ibrokhimov Botirjon

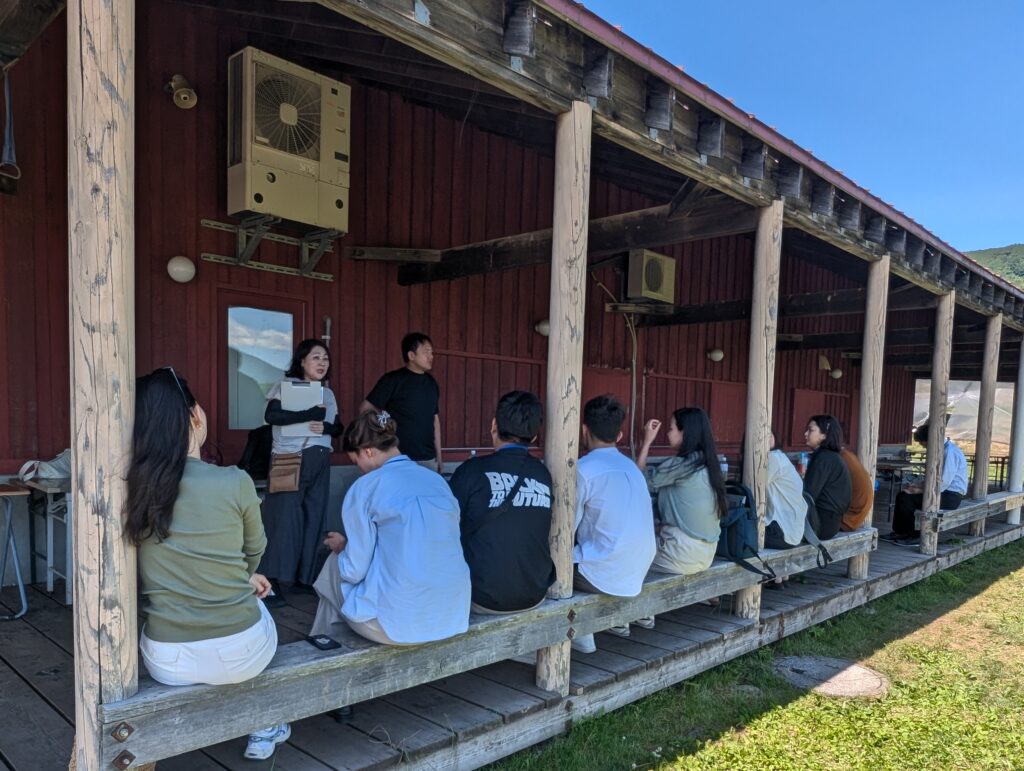

As part of a field research trip with my SPJES cohort from the University of Tsukuba, our group traveled to the Niseko region of Hokkaido in July 2025. Our objective was to observe and analyze the real-world application of sustainable development principles in a region famed for its world-class ski resorts but facing the complex socio-economic pressures of rapid, internationalized growth. While our itinerary included meetings with government officials and sustainability coordinators, our visit to the Niseko Takahashi Dairy Farm offered a particularly compelling case study. It allowed us to examine Japan’s “Sixth Sector Industrialization” policy not as an abstract concept, but as a living, breathing business model that has fundamentally reshaped a family farm and its role within the community.

The farm’s reputation certainly preceded it—many of us were anticipating the “legendary” Hokkaido soft-serve ice cream (figure 1, a)—but our primary goal was to deconstruct the innovative model that made such quality possible. What we found was a story of resilience, entrepreneurial learning, and a deep commitment to community, all set against one of the most stunning landscapes in Japan (figure 1, b).

Upon arrival, the first thing one notices is the breathtaking scenery. The farm is laid out across a verdant landscape, with fields of corn and flowers stretching towards the iconic, conical shape of Mt. Yotei. The farm itself is a welcoming cluster of red-roofed wooden buildings, including various “Kobo” (workshops) for processing milk, yogurt, cheese, and cakes. An old red tractor sits in the pasture (figure 1, a), a photogenic nod to the farm’s agricultural roots. This carefully cultivated environment is the tertiary, or service, component of the farm’s business model in action, transforming it from a simple production site into a tourism destination.

The farm’s evolution, as was explained to us during the lecture “Challenges to the Sixth Sector Industry” conducted by Mr. Kei TAKAI outside (viewing the mount Yotei), is a direct response to documented economic pressures. Like many agricultural enterprises in Japan, the Takahashi family faced declining agricultural incomes in the 1990s and decreasing demand for raw milk. It was under the leadership of the current president, Mr. Mamoru Takahashi, who took over in 1970, that the farm began its strategic pivot away from being solely a primary producer.

This strategy is a textbook example of Sixth Sector Industrialization, or “AFFriinnovation,” a term that describes the vertical integration of the primary (production), secondary (processing), and tertiary (service) sectors. Our visit allowed us to observe this model empirically. During the free time, I have got to see the cows and fields (primary). As a group, we observed the workshops where cheese and yogurt were made (secondary), and the cafes and shops where the final products were sold (tertiary). The “Mandriano” pizzeria, using cheese from the adjacent “Cheese-Kobo,” serves as a tangible—and delicious—example of this synergy. The pizza our group shared, hot from a wood-fired oven, was a direct product of this integrated system.

This successful model was not achieved overnight. The farm’s history is one of iterative development and learning from failure. We learned that an early attempt at cheese production in the late 1990s was unsuccessful, and a retail expansion into Tokyo’s Kichijoji district had to be closed after only two years. Even though, the farm’s success with products like its “Nomu Yoghurt” and its on-site restaurants is a good model to learn.

From an analytical perspective, the farm’s operations contribute significantly to several key Sustainable Development Goals, providing a powerful local solution to regional and global challenges. For example, in term of SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) & SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), one of the most pressing issues in the Niseko area is its reliance on a seasonal tourism economy, which leads to precarious employment. From the materials provided for my visit, I noted that Takahashi Dairy Farm provides stable, year-round employment for 60 people. This creates decent work and fosters a more resilient local economy. Furthermore, by processing its own raw milk and sourcing other ingredients locally for its restaurants, it strengthens local supply chains, promotes responsible consumption, and reduces the carbon footprint associated with food transportation.

The farm’s most popular product (at least, popular for me), its soft-serve ice cream, can be understood as the success of this model. Its exceptional quality, which we enthusiastically confirmed, is a direct result of the immediate availability of fresh, self-produced milk (a tangible benefit of vertical integration that cannot be easily replicated by competitors who rely on complex supply chains).

Perhaps the most compelling finding of our visit was the realization that Mr. Takahashi’s vision extends beyond his farm’s fences. He is also the President of Niseko Machi Co., Ltd., the public-private entity leading the “Niseko Mirai” sustainable community project. This ambitious initiative, which aims to build an affordable and eco-friendly town for 450 residents, is a direct response to the housing crisis created by the tourism boom. This demonstrates an extraordinary level of commitment to the long-term well-being of the Niseko community. It is a practical application of what my research report identified as a “trialogue”—a constructive collaboration between the private sector, public officials, and civil society to solve complex local problems.

Overall, the Takahashi Dairy Farm is a powerful case study which demonstrates that entrepreneurial innovation, when grounded in a commitment to quality and community, as well as the concept of “AFFriinovation”, can turn out to become both sustainable and pretty much profitable business.